A first-person account by Allison Herens, the Health Department’s first-ever Harm Reduction Coordinator:

Long before becoming a Harm Reduction Coordinator and before it became the topic of every news headline internationally, I knew there was an opioid crisis. Growing up in Camden County, NJ, I was only sixteen years old when the first person I knew died of an opioid overdose. By the time I graduated from high school, many of my friends and loved ones were grappling with addiction to opioids. When I needed it most, I didn’t even know what naloxone was, let alone where to get it and how to use it. I didn’t know how to prepare for the worst- I simply lived in fear. I’m thankful that when the time finally came to act, I was ready.

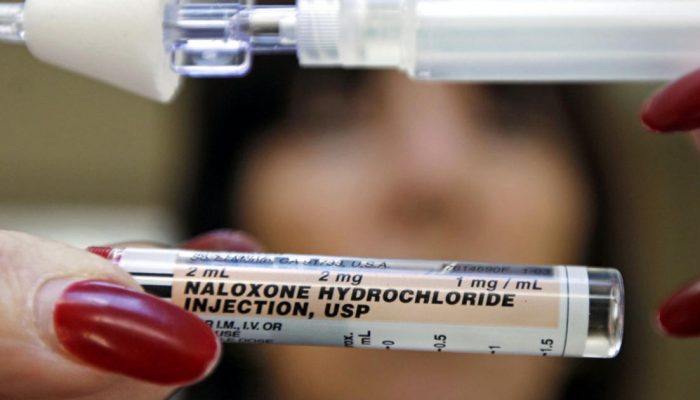

As part of the City’s response to this crisis, I have been appointed Harm Reduction Coordinator, a newly created position to combat fatal opioid overdoses through education and distribution of naloxone, a life-saving medication that reverses opioid overdoses. One of the first things I did in this job was going to a pharmacy in Center City to see what it was like to buy naloxone using Pennsylvania’s Standing Order. I never imagined that I would have to actually use it, nor so soon.

After attending my second overdose prevention training at Prevention Point the very next day, I encountered an individual experiencing an overdose on the platform at the Somerset station on the El. I had never been so grateful to not only know what to do in that situation, but to also have already physically gotten the medication that ultimately saved that man’s life. Family, friends, and colleagues have praised my actions as “heroic” but I hope that I can ultimately serve as an example for others.

When the worst happened and it was life or death, being ready with naloxone saved a life

Our goal is to put naloxone in the hands of everyone who is at risk of having an overdose or likely to see one. We have partnered with SEPTA Police, the Philadelphia Department of Prisons, and community organizations like Prevention Point, Angels in Motion, and Project SAFE, and they have helped us distribute nearly 5,000 doses of naloxone so far. Since SEPTA officers began carrying naloxone in September, they have successfully reversed 30 overdoses while the Philadelphia Department of Prisons is now giving it at discharge to those who self-report injection drug use.

Despite these efforts, I worry about the growing crisis. A recent article showed that during the first half of 2017, fatal overdoses increased by 58 percent. Community organizations throughout the city are demanding naloxone, and we’re trying to get it out to them. This growing need highlights my second focus: education. Most people either don’t know about naloxone, or have wrong information about it. By offering more training across the city, we hope to not only educate the public and bring awareness to the issue, but also to encourage regular folks to use the Standing Order and carry naloxone.

Do I think every single person in the city is going to carry it? Probably not, but I’m hopeful that the more people we educate and the more people that are willing carry it, the more lives we can save.