This blog post was written by Rev. Naomi Washington-Leapheart, Director for Faith-Based and Interfaith Affairs, Office of Public Engagement

When I first moved to Philadelphia to participate in a pre-freshman summer program at the University of Pennsylvania more than 20 years ago, I was eager to get to know the landscape of the city. I signed up to participate in a scavenger hunt that sent us looking for the answers to questions about historical and significant places scattered throughout Center City and West Philadelphia. As we searched, my church-girl heart swelled with joy when I saw that nearly every corner we rounded was anchored by a house of worship.

The recent premiere of the documentary, The Black Church: This is Our Story, This is Our Song, on WHYY-TV gives us an opportunity to consider and celebrate the extraordinary impact of Black faith and Black faith institutions on American life. From gathering in “invisible” hush harbors despite the chains of enslavement to assembling by the thousands in digital worship during the COVID-19 pandemic, Black people have kept the faith—in our own agency and in a transcendent power—that makes it possible for us to experience joy and freedom regardless of our circumstances. This Black history month, we celebrate the significant contributions of the Black faithful in the Philadelphia area.

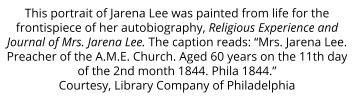

A First of Firsts: Jarena Lee

Jarena Lee was born to free Black parents on February 11, 1793 in Cape May, New Jersey. Though her family was not enslaved, their economic situation required Jarena to begin work as a “live-in servant” for a white family at age seven. Lee moved to Philadelphia as a teenager and continued domestic work. Though Lee’s parents did not provide religious instruction, she was later exposed to Christian teachings at Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, (now Mother Bethel AME) where Reverend Richard Allen, the founder of the AME denomination, preached.

In 1807, Lee heard the voice of God commissioning her to preach. She revealed to her pastor this confident call to preaching. Allen initially denied Lee’s request, citing Methodist discipline, which banned women preachers.

In 1811, Lee married Reverend Joseph Lee, the pastor of Mt. Pisgah Methodist Society at Snow Hill (now the Mt. Pisgah AME Church of Lawnside). During their marriage her husband did not want her to preach, so she felt forced to put her spiritual needs on hold. But after Joseph’s death in 1818, Lee once again sought Richard Allen’s permission to preach publicly. He continued to deny her request.

One Sunday in 1819, during a worship service at Mother Bethel AME, the guest preacher, Reverend Richard Williams, was unable to speak the words he had prepared. Jarena Lee rose from her seat and addressed the congregation. After hearing her preach that day, Bishop Allen changed his mind, and officially authorized the 36-year-old Lee to preach and hold prayer meetings. The first Black woman to preach the Christian gospel publicly, Lee wrote that she “traveled two thousand three hundred and twenty-five miles, and preached one hundred and seventy-eight sermons” to racially-mixed audiences in private homes, schools, public meeting houses, open fields, and a variety of Christian congregations mid-Atlantic states, lower Canada, Cincinnati, Detroit, and New England. She raised money for and even planted churches during a time when slavery was legal and Black women could neither vote nor own property. Her diary records one meeting for which enslaved Black people had walked 20 miles and more to hear her preach.

Jarena Lee’s preaching ministry lasted for more than 20 years until illness slowed her. In addition to her work in ministry, she was also heavily involved in the abolitionist movement and joined the American Antislavery Society in 1839. In 2016, Jarena Lee’s call to preach was officially recognized by the AME Church, which ordained her posthumously during their 50th Quadrennial Session of the General Conference.

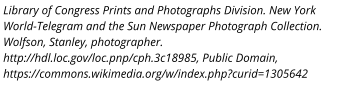

Gay, Black, and Quaker: Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin was a leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, pacifism and non-violence, and LGBTQ+ rights. Born and raised in West Chester by his maternal grandparents, Julia Davis Rustin and Janifer Rustin, Rustin was a star student at West Chester High School (now Henderson), where he played football and ran track, participated in French, classics, and science clubs, and excelled in singing and oratorical and essay contests. Situated between his grandparents’ very different religious traditions, Bayard developed his passion for protest during services at Bethel AME Church and his principled ideas about strategic nonviolence at Quaker meetings.

Bayard Rustin was a leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, pacifism and non-violence, and LGBTQ+ rights. Born and raised in West Chester by his maternal grandparents, Julia Davis Rustin and Janifer Rustin, Rustin was a star student at West Chester High School (now Henderson), where he played football and ran track, participated in French, classics, and science clubs, and excelled in singing and oratorical and essay contests. Situated between his grandparents’ very different religious traditions, Bayard developed his passion for protest during services at Bethel AME Church and his principled ideas about strategic nonviolence at Quaker meetings.

After attending both Wilberforce University (where he was expelled for organizing a strike) and Cheyney State Teachers College (now Cheyney University of Pennsylvania), Rustin moved to New York, where he deepened his commitment to Quaker values and worked for the American Friends Service Committee and the Fellowship of Reconciliation.

Faithful to his pacifist commitments, he was imprisoned for two years – from 1944 to 1946 – for refusing the draft during World War II. By the 1950s, Bayard was a leader in the rising Civil Rights Movement; he was an advisor to Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and was the chief architect of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. During the last two decades of his life, Bayard Rustin continued to work tirelessly as a “roving ambassador” for global and national liberation movements.

Despite the fact that he played such an important role in global movements, Rustin “faded from the shortlist of well-known civil rights lions,” in large part because of public discomfort with his out and proud identity as a gay man. However, the 2003 documentary film Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin, a Sundance Festival Grand Jury Prize nominee, and the March 2012 centennial of Rustin’s birth helped to renew and sustain his legacy. On November 20, 2013, President Barack Obama posthumously awarded Rustin the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Bayard Rustin’s spiritual and political formation in Chester County paved the way for his pursuit of equal rights for all people.

Black FaithPHL Today: The Muslim Wellness Foundation and Jews in ALL Hues

Today, many Black people in Philadelphia continue our ancestral legacies by creating and leading reflective, justice-centered, deeply faithful lives. Here are short profiles of two extraordinary organizations that are led by Black leaders who serve on the Mayor’s Commission for Faith-Based and Interfaith Affairs:

Jews in ALL Hues (JIAH) is an education and advocacy independent 501(c)(3) organization that supports Jews of Color and multi-heritage Jews. Founded by Jared Jackson, who also serves as Executive Director, JIAH’s goal is to build a future for the Jewish people where intersectional diversity and dignity are normative. To achieve this vision, the organization leads workshops and consultations, conducts research and assessment, and hosts events.

Muslim Wellness Foundation (MWF), a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization established in 2011 by Founder and President, Dr. Kameelah Mu’Min Rashad, PsyD., uses an interdisciplinary spiritually-relevant, community-based public health framework to reduce stigma associated with mental illness, addiction and trauma in the American Muslim community through dialogue, education and training. Since 2015, MWF has hosted the Annual Black Muslim Psychology Conference, and over the past year, MWF has successfully provided resources and leadership in response to the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by co-convening the National Black Muslim COVID Coalition. This Coalition has served communities across the country through surveys, webinars, and networking.

Muslim Wellness Foundation (MWF), a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization established in 2011 by Founder and President, Dr. Kameelah Mu’Min Rashad, PsyD., uses an interdisciplinary spiritually-relevant, community-based public health framework to reduce stigma associated with mental illness, addiction and trauma in the American Muslim community through dialogue, education and training. Since 2015, MWF has hosted the Annual Black Muslim Psychology Conference, and over the past year, MWF has successfully provided resources and leadership in response to the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by co-convening the National Black Muslim COVID Coalition. This Coalition has served communities across the country through surveys, webinars, and networking.

Watch The Black Church: This is Our Story. This is Our Song. streaming now on WHYY or on PBS.org .